Principles in Pharmacophore Elucidation¶

Info

The analytical process and underlying principles of the pharmacophore-based drug design approach are presented and discussed. The strengths and limitations of the method are discussed and illustrated with examples.

Number of Pages: 96 (±2 hours read)

Last Modified: January 2009

Prerequisites: Principles of Rational Drug Design

Introduction¶

Pharmacophore-Based Drug Design¶

Pharmacophore based drug design allows the creation of new lead molecules based on already known biologically active molecules.

Operational Strategy: Molecular Mimicry¶

This approach consists of mimicking the structural features of a reference compound. The central question is which elements should be mimicked in order to obtain biologically active molecules? Should all the elements be mimicked or only a part of the reference compound?

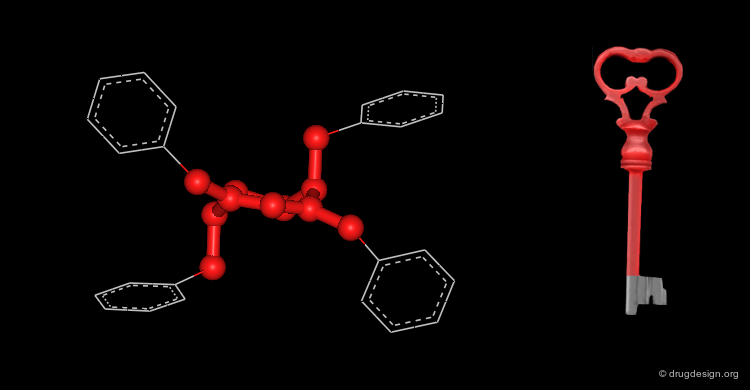

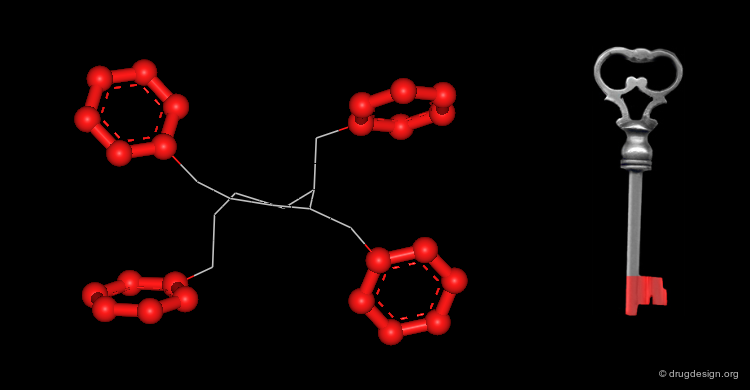

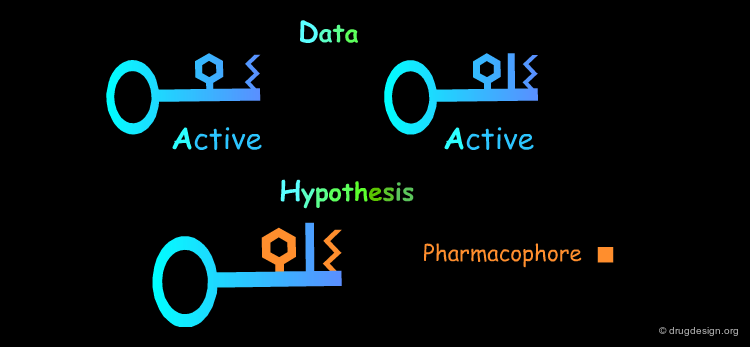

Analogy with Keys¶

Similar to a key that activates a mechanical lock, some of the elements of a biologically active molecule are essential while others are not. One of the roles of the non-essential elements is to hold the essential elements in the proper 3D geometrical orientation.

Active Molecules are Complicated Keys¶

In a key, the "handle" is separate from the "teeth" and the "teeth" open the lock. In an active molecule, this may not be the case. The "handle" can have essential elements while the "teeth" may have elements that are not essential in activating the "lock". The following example shows a molecule with a "handle" containing two essential functional groups (carbonyl and N-H) as well as an element of the "teeth" (phenyl group) that is not essential. The pharmacophore is defined by all the structural elements that are essential for the specified biological activity.

Definition of a Pharmacophore¶

A pharmacophore can be defined as a specific 3D arrangement of chemical groups common to active molecules and essential to their biological activities.

articles

Present Status of Chemotherapy Ehrlich, P. Chem. Ber. 42 1909

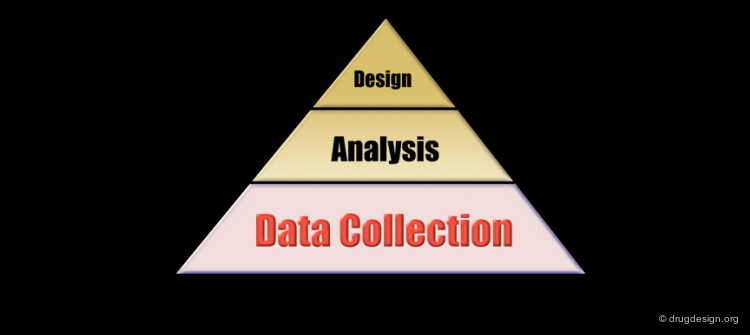

Analytical Process¶

The Analytical Process¶

Pharmacophore-based drug design includes the following three steps: gathering all relevant information (Data Collection), in depth analyses of the information (Analysis) and finally the design of new molecules based on the analysis (Design).

Data Collection Stage¶

Data collection consists of gathering of all available information from various sources: publications, conferences, patents, chemical formulas, biological activities, x-ray data, in-house HTS information, kinetic studies and mechanism of actions. The importance of this stage should not be underestimated. All development that follows will be highly influenced by the information collected.

Analysis Stage¶

Now that the raw data has been collected, one must produce additional data that can be deduced from the existing information. The proper development of in depth analyses generates new knowledge, hypotheses and the establishment of a logical link between the different components of the information. The aim of the analysis is to create a framework that integrates the knowledge deduced from the structural elements that are essential for the biological activities and from the stereochemical features of the receptor site.

Design Phase¶

When links between the structural features of the molecules and their biological properties have been established, the design process can begin. Designing consists of creating new molecules conforming to the desired structural requirements previously specified. For example, a design may incorporate the pharmacophore derived from the known active molecules into the structure of new compounds.

Simple Case¶

Introduction with a Simple Case¶

Let's suppose we have two chemically unrelated molecules that are very potent biologically and act according to the same mechanism of action and let's assume that we know their bioactive conformations. The following are the different steps in analyzing this simple problem:

Molecular Similarity¶

Since both molecules are biologically active, we can deduce that they share the same essential pharmacophoric elements. The central problem is to reveal them.

articles

Similarity and Dissimilarity: a Medicinal Chemist's View Kubinyi H Persp. Drug Discov. Des. 9-11 1998

Molecular Similarity and Dissimilarity Richards WG Molec. Eng. 5 1995

Similarity in Chemistry: Past, Present and Future Rouvray DH Top. Curr. Chem. 173 1995

Why do we Need so Many Chemical Similarity Search methods? Sheridan RP and Kearsley SK Drug Discov. Today 7 2002

book

Dean PM Molecular Similarity in Drug Design Blackie Academic & Professional, Chapman & Hall 1995

Doucet J-P and Weber J Computer-Aided Molecular Design, Theory and Applications Academic Press 1996

Concept and Application of Molecular Similarity John Wiley & Sons 1990

Difficulty to Identify Common 3D Features¶

In the following example, it is very difficult to identify the common features by just looking at the three dimensional representations.

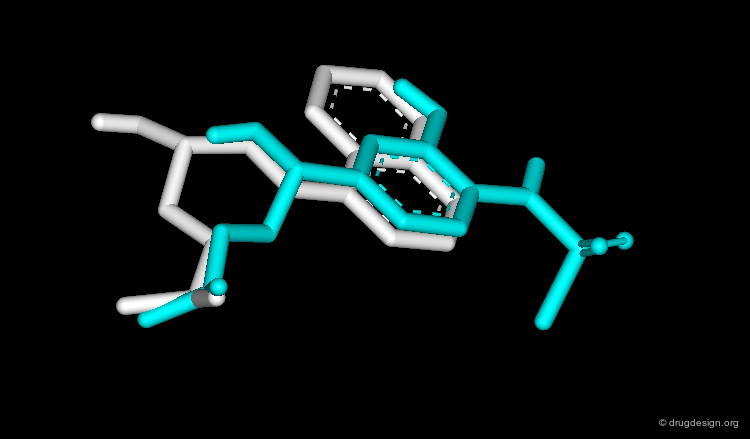

Superimpositions¶

The easiest way to identify common 3D features in a series of molecules is to "superimpose" them. When chemically unrelated compounds are compared, superimposition techniques are extremely useful. Note that the word "superimposition" can be used interchangeably with the word "alignment". They both refer to the same technique.

Goal of Superimposition Procedures¶

Superimposition reveals the similarities and differences between molecules. 3D structural similarities and dissimilarities are easily identified and utilized to interpret the biological properties of the molecules concerned.

Summary of the Example¶

Let us summarize the different steps considered in our example: we started with two active molecules for which we knew their mode of action and their bioactive conformations. We wanted to find the common structural features shared by the molecules and used superimposition techniques to reveal them. This paved the way for additional insights by analyzing both molecules in terms of their essential and non-essential structural moieties, the exact relative location of the structural elements that carry the biological activities, and their intrinsic physico-chemical properties.

Superimposition Technique¶

The superimposition of two molecules, which are two rigid objects, is done in the following way: the pairs of atoms to be superimposed are listed. One molecule is fixed and the second moves to a new position that corresponds to the minimum of the sum of the squared distances between the atom pairs. A minimum of three pairs of atoms must be listed.

articles

A Solution for the Best Rotation to Relate Two Set of Vectors Kabsch W Acta Cryst. A. A32 1976

Superimposition Technique: Results¶

The picture shows the two molecules superimposed. A numerical value named "RMS" (root mean square) is associated with a given superimposition. The smaller the number, the better the fit between the selected pairs of atoms.

Dummy Atoms¶

It is sometimes very helpful to use "dummy atoms" associated to a molecule as points to be used for the superimpositions. For example a dummy atom located at the center of a phenyl ring can be used to define all the atoms of the ring; such dummy atoms are also called "centroids".

Typical Example¶

A More Typical Example¶

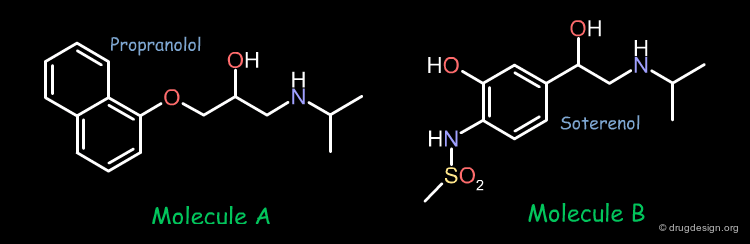

In pharmacophore-based projects, the bioactive conformations of the individual molecules are generally not known, only their chemical formulas and associated biological activities represent all the data that is available. A project could start with two molecules. For example the two following compounds showed good biological activities in a given project.

Identification of the Bioactive Conformation¶

In order to develop the same approach as the one presented in the previous example, we have to find the bioactive conformation of each molecule. The conformational analysis of the two molecules show that they have 972 and 648 preferred conformers respectively. The question is which one of these conformers is the bioactive form.

Conformers of Molecule A¶

The following contains the first 100 conformers for molecule A.

Conformers of Molecule B¶

The following contains the first 100 conformers for molecule B.

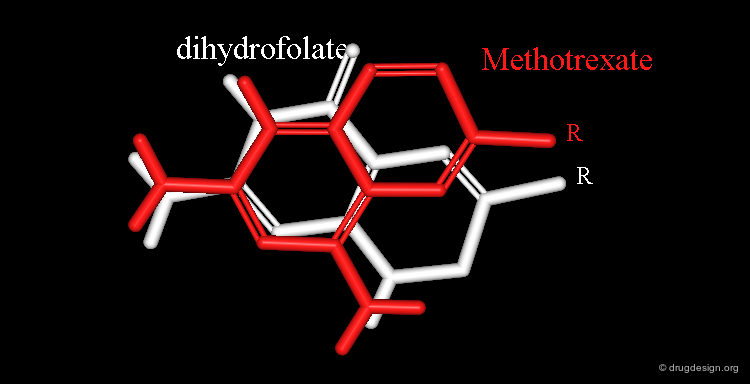

Bioactive Conformation: Geometry¶

Experience shows that the geometry of the bioactive conformation of a molecule can be very far from the conformation of the isolated molecule in solution or in the crystal. The example shown here illustrates the case of methotrexate where the conformation of the free molecule is shown in red, and in blue when the molecule is bound to its biological target.

articles

A Study into the Effects of Protein Binding on Nucleotide Conformation Moodie SL and Thornton JM Nucleic Acids Res. 21 1993

Conformational Changes of Small Molecules Binding to Proteins Nicklaus MC, Wang S, Driscoll JS and Milne GW Bioorg. Med. Chem. 3 1995

Experimental Determination of Oligosaccharide Three-Dimensional Structure Rice KG, Wu P, Brand L and Lee YC Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3 1993

Comparison of Conformations of Small Molecule Structures from the Protein Data Bank with those Generated by Concord, Cobra, ChemDBS-3D, and Converter and those extracted from the Cambridge Structural Database Ricketts EM, Bradshaw J, Hann M, Hayes F, Tanna N, and Ricketts DM J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci 33 1993

Bioactive Conformation: Energy¶

It has been shown that the difference of energy between the bioactive conformation of a molecule and the global minimum conformation of the isolated molecule is generally less than 12 kJ/mol (3 kcal/mol).

Reduction of the Complexity¶

This observation allows us to filter and reject a great number of conformations that cannot represent the bioactive geometry. This is schematically illustrated in the following diagram. At this stage the number of conformations is greatly reduced.

Bioactive Conformations Must be Superimposable¶

After having eliminated high energy conformers, we can now consider to identify in the remaining set of low energy conformations, the probable bioactive geometry of our molecules. Knowing that both compounds bind to the same active site of the biological receptor, we can hypothesize that their bioactive conformations must share common 3D features.

Systematic Superimposition of Conformers¶

To identify the probable bioactive conformations of the two molecules, all pairs of conformers are superimposed. By assessing the quality of the different superimpositions, this systematic search allows one to find the one that presents a maximum of similarity between the two molecules. The conformers that are present in this superimposition are the probable bioactive conformations of the two molecules.

articles

Identification of Common Functional Configurations among Molecules Barnum D, Greene J, Smellie A, and Sprague P J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 36 1996

Sampling Conformational Hyperspace: Techniques for Improving Completeness Dammkoehler RA, Karasek SF, Shands EF,and Marshall GR J Comput. Aided. Mol. Des 9 1995

Compass: A Shape-Based Machine Learning Tool for Drug Design Jain AN, Dietterich TG, Lathrop RH, Chapman D, Critchlow RE Jr, Bauer BE, Webster TA and Lozano-Perez T J. Comp. Aided Mol. Des. 8 1994

A Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Molecular Overlay and Pharmacophore Elucidation Jones G, Willett P, and Glen RC J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 9 1995

Different Approaches toward an Automatic Structural Alignment of Drug Molecules: Applications to Sterol Mimics, Thrombin and Thermolysin Inhibitors Klebe G, Mietzner T and Weber F J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 8 1994

Time-Efficient Flexible Superposition of Medium-Sized Molecules Lemmen C and Lengauer T J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11 1997

A Fast New Approach to Pharmacophore Mapping and its Application to Dopaminergic and Benzodiazepine Agonists Martin YC, Bures MG Danaher EA, DeLazzer J, Lico I and Pavlik PA J Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 7 1993

Molecular Shape Comparison of Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists Masek BB, Merchant A and Matthew JB J. Med. Chem. 36 1993

Flexible Matching of Test Ligands to a 3D Pharmacophore Using a Molecular Superposition Force Field: Comparison of Predicted and Experimental Conformations of Inhibitors of Three Enzymes McMartin C and Bohacek RS J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 9 1995

A Molecular Field-Based Similarity Approach to Pharmacophoric Pattern Recognition Mestres J, Rohrer DC, and Maggiora GM J. Mol. Graph. Model. 15 1997

SQ: A Program for Rapidly Producing Pharmacophorically Relevant Molecular Superpositions Miller MD, Sheridan RP, and Kearsley SK J. Med. Chem. 42 1999

Molecular Surface-Volume and Property Matching to Superpose Flexible Dissimilar Molecules Perkins TD, Mills JE, and Dean PM J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 9 1995

MEPSIM: a Computational Package for Analysis and Comparison of Molecular Electrostatic Potentials Sanz F, Manaut F, Rodriguez J, Lozoya E, and Lopez-de-Brinas E J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 7 1993

The Ensemble Approach to Distance Geometry: Application to the Nicotinic Pharmacophore Sheridan RP, Nilakantan R, Dixon JS, and Venkataraghavan R J Med Chem. 29 1986

book

Itai A, Tomioka N, Yamada M, Inoue A, and Kato Y In: 3D QSAR in Drug Design ESCOM 1993

Mason JS Molecular Similarity in Drug Design Blackie Academic & Professional, Chapman & Hall 1995

Results with High Informational Content¶

At this stage the two bioactive conformations are identified. The superimposition of the molecules reveals the common structural moieties and differences, information of central importance for further design of new lead compounds.

articles

Adrenergic Agents. 4 Substituted Phenoxypropanolamine Derivatives as Potential β-Adrenergic Agonists Kaiser C, Jen T, Garvey E, Bowen WD, Colella DF, and Wardel JR Jr J. Med. Chem. 20 1977

Summary¶

In summary: (1) the conformational analyses of the active molecules were undertaken, they allowed the generation of a great number of probable conformations; (2) conformations of high energies (above 12 kJ/mol) were rejected; (3) the systematic superimposition of all the remaining conformations was conducted; (4) the candidate bioactive conformations of each active molecule was revealed; (5) all these steps pave the way for further analyses.

Complexity Levels¶

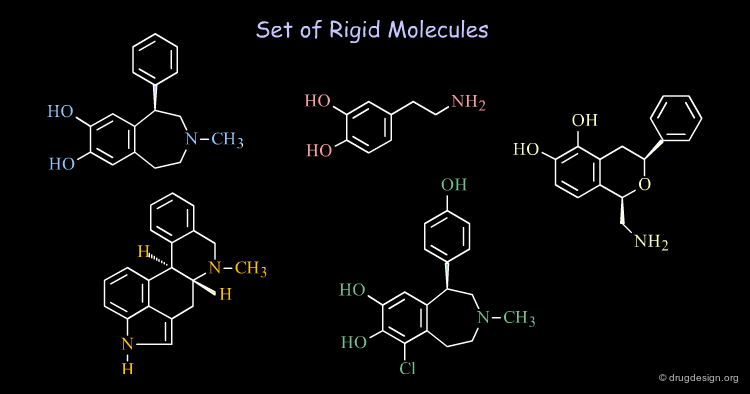

Rigid and Flexible Molecules¶

A molecule with only several rotatable bonds can have thousands of possible conformations. Revealing the bioactive conformations of very flexible molecules may be extremely complicated. When the molecules are relatively rigid (e.g. with cyclic constraints), the treatments are easier to undertake and allow the rapid generation of data of high informational content.

Bioactive Conformation of GABA¶

Finding the bioactive conformation of a given active molecule may be very complex. We have to use all the information contained in the data accumulated in order to deduce possible solutions. The following molecule (GABA, an important neurotransmitter) is a flexible molecule. The design of CNS agents, based on this compound, requires a good knowledge of its bioactive conformation.

articles

The Action of Conformationally Restricted Analogues of GABA on Limulus and Helix central Neurones James VA, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, and Walker RJ Experientia 34 1978

A New Class of GABA Agonist Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Johnston AR, Lodge D, and Curtis DR Nature 268 1977

Methyl Analog of GABA¶

The methyl analogue has good activities. However, this information is not sufficient to assign unambiguously the bioactive conformation of the neurotransmitter when it binds to its receptor.

Muscimol is a GABA Agonist¶

Muscimol is an agonist that activates the GABA receptor. The torsional constraints present in this molecule reveal a great portion of the bioactive geometry of GABA.

THIP is a GABA Agonist¶

THIP is also a GABA agonist. This observation allows us to clearly identify the exact molecular geometry of GABA when this neurotransmitter binds to its receptor.

The Deduced Bioactive Conformation of GABA¶

GABA, Muscimol and THIP are in their bioactive conformations. They all enable us to unmistakably identify the exact bioactive conformation of GABA when it activates the GABA-A receptors.

Superimposition in the Space of Properties¶

In general, we align molecules on the basis of their atomic positions. In fact, one should superimpose the spatial arrangement of their physical and chemical properties.

articles

Identification of Common Functional Configurations among Molecules Barnum D, Greene J, Smellie A, and Sprague P J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 36 1996

Utilization of Gaussian Functions for the Rapid Evaluation of Molecular Similarity Good AC, Hodgkin EE, and Richards WG J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 32 1992

Structure-Activity Relationships from Molecular Similarity Matrices Good AC, So SS and Richards WG J. Med. Chem. 36 1993

Optimization of Carbo Molecular Similarity Index Using Gradient Methods McMahon AJ and King PM J. Comput. Chem. 18 1997

A Molecular Field-Based Similarity Approach to Pharmacophoric Pattern Recognition. Mestres J, Rohrer DC, and Maggiora GM. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 15 1997

A Receptor Model for Tumor Promoters: Rational Superposition of Teleocidins and Phorbol Esters Itai A, Kato Y, Tomioka N, Iitaka Y, Endo Y, Hasegawa M, Shudo K, Fujiki H and Sakai SI Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85 1988

Automatic Superposition of Drug Molecules Based on Their Common Receptor Site Kato Y, Inoue A, Yamada M, Tomioka N and Itai A J. Comput. Aided Molec. Des. 6 1992

A Novel Method for Superposing Molecules and Receptor Mapping Kato Y, Itai A and Iitaka Y Tetrahedron 22 1987

An Alternative Method for the Alignment of Molecular Structures: Maximizing Electrostatic and Steric Overlap Kearsley SK and Smith GM Tetrahedron Comput. Method. 3 1990

Different Approaches toward an Automatic Structural Alignment of Drug Molecules: Applications to Sterol Mimics, Thrombin and Thermolysin Inhibitors Klebe G, Mietzner T and Weber F J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 8 1994

Time-Efficient Flexible Superposition of Medium-Sized Molecules Lemmen C and Lengauer T J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11 1997

Molecular Shape Comparison of Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists Masek BB, Merchant A and Matthew JB J. Med. Chem. 36 1993

Alignment of Molecules by the Monte Carlo Optimization of Molecular Similarity Indices Parretti MF, Kroemer RT, Rothman JH, and Richards WG J. Comput. Chem. 18 1997

Molecular Surface-Volume and Property Matching to Superpose Flexible Dissimilar Molecules Perkins TD, Mills JE, and Dean PM J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 9 1995

MEPSIM: a Computational Package for Analysis and Comparison of Molecular Electrostatic Potentials Sanz F, Manaut F, Rodriguez J, Lozoya E, and Lopez-de-Brinas E J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 7 1993

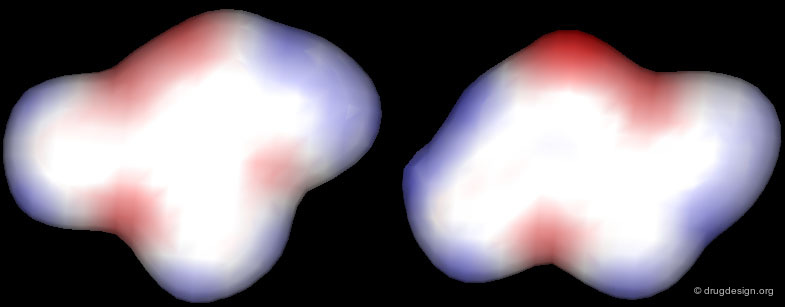

Example of Superimposition in the Space of Properties¶

Dihydrofolate and methotrexate bind to the catalytic site of the dihydrofolate reductase. Both have a rather long side chain (R) that is the same in the two molecules.

articles

Automatic Search for Maximum Similarity between Molecular Electrostatic Potential Distribution Manaut F, Sanz F, Jose J and Milesi M J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 5 1991

book

Manaut F, Lozoya E and Sanz F QSAR: Rational Approaches to the Design of Bioactive Compounds Elsevier Science Publ. B.V. 1991

Alignment Based on the 2D Formulas¶

By observing their chemical formulas, it is obvious that these two structures can be aligned in the following way:

Different Electrostatic Distribution in 2D Alignment¶

However, this is not observed experimentally. Notice that in this alignment the electrostatic features of the two molecules are not the same.

Alignment Based on 3D Structures of Complexes¶

The crystallographic structures of the complexes of the enzyme with dihydrofolate and with methotrexate were determined, methotrexate was found to be protonated. The X-ray results reveal a correspondence between the two ligands that is not obvious by the mere consideration of the chemical structures of the two molecules.

Correct Alignment: Similar Electrostatic Distribution¶

The correct alignment becomes clearer when looking at the 3D distribution of their electrostatic potential profiles. Accessing molecules in the space of their 3D physicochemical properties is the best way to identify the proper alignment of chemically unrelated molecules.

Principles of Analysis¶

Complexity of Analyses (1/3)¶

When superimpositions are obtained, the molecular modeler acquires a vast amount of data due to the conformational complexity of the molecules. However, his analyses are far from being complete. To methodically pursue them, he should assess the validity of the superimpositions, review their consistency with all the available data, define pharmacophores, consider different working hypotheses,?

Complexity of Analyses (2/3)¶

... challenge them by making a note of all data that favor or contradict a given hypothesis, define molecules that offer the possibility of refining a given hypothesis, assign weight to data that supports the hypotheses, and finally undertake computerized treatments for generating novel information.

Complexity of Analyses (3/3)¶

Using common sense and intuition, they must combine all the knowledge acquired in the course of the analyses to decide which is the preferred model. Only when analysis has fully utilized all the content of the data, can the design phase and its associated operational strategies begin.

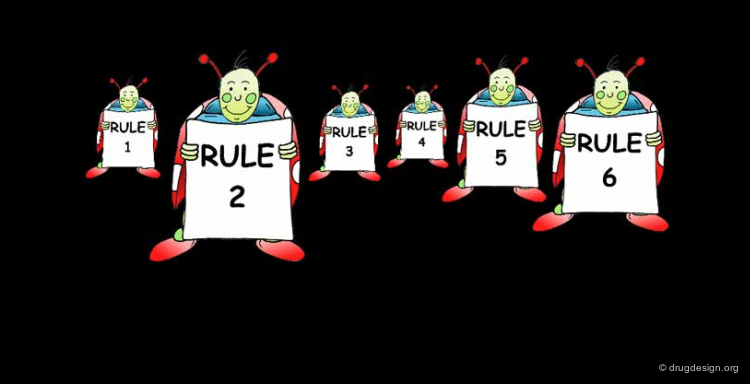

Six Rules for Analyses¶

In order to better understand the logical developments that might take place in the course of the analyses, let us come back to the analogy with keys and distinguish six different situations that we may typically encounter.

Common Structural Features: Rule 1¶

The analysis of the structural features of a set of biologically active molecules acting with the same mechanism of action consists of identifying the structural elements that are essential for the activity of the molecules (pharmacophore). The comparison of structural features in molecules is a key topic in cheminformatics and is called "Molecular Similarity".

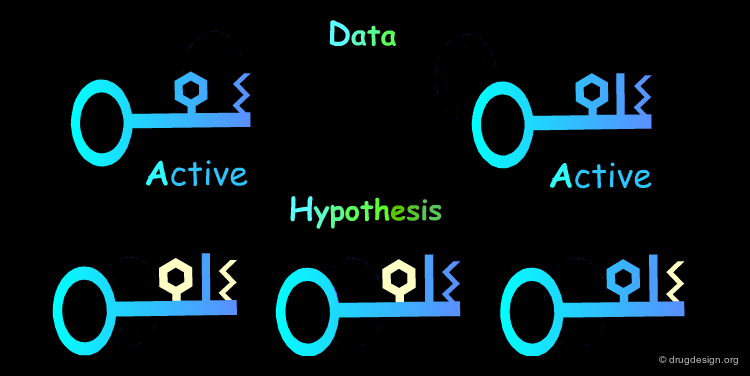

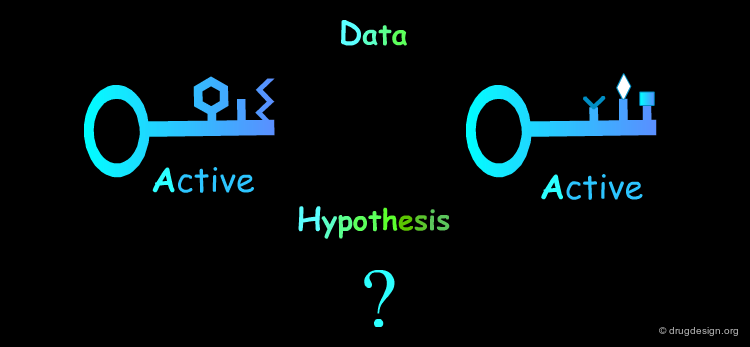

Multiple Hypotheses: Rule 2¶

The Identification of common structural features can lead to many hypotheses. The following active keys lead to three distinct hypotheses. Additional information needs to be generated in order to meet a unique solution.

Inactive Molecules: Rule 3¶

Inactive molecules may be of high informational content and play an important role in the analysis. In the example below the inactive molecules allow the refinement of the hypothesis.

Closely Related Molecules: Rule 4¶

Closely related molecules with similar properties are of poor informational content.

Molecules With No Common Features: Rule 5¶

Molecules that are structurally too diverse are difficult to be exploited. To get interpretable data the chemist must generate molecules with single structural modifications. When the molecules are structurally different, advanced cheminformatics (conformational analyses) and in depth modeling analyses need to be done.

Mapping the Receptor: Rule 6¶

The analysis of active/inactive molecules aims at generating a picture of the receptor enabling to understand its stereochemical requirements. For example if removing a structural element in the molecule leads to the complete loss of the biological activity, this may indicate the existence of an important interaction with the receptor. If the introduction of an additional fragment in a molecule leads to loosing its biological activity, this may indicate the existence of a non-favorable interaction with the receptor (e.g. steric bump).

Conformational Control¶

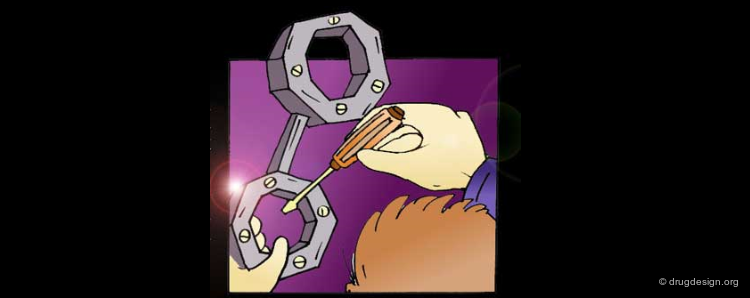

Control of the Molecular Geometries¶

Drug design analyses require perfect control of the conformational features of the molecules considered. The molecular modeler needs to have a perfect understanding of the conformational features in order to manipulate them with his own hands in 3D. For him the presence of structural features such as rings or rotatable bonds in the molecules should not present a problem. They must be under good control for analyzing the SAR (Structure-Activity Relationships) implications and later be utilized for the design stage. Advanced computerized tools can assist him. However, it is his ability to predict, modify, and anticipate the conformational behavior of a molecule's related analog that is of utmost importance.

3D Considerations¶

In the great majority of cases, it is only when the set of active molecules are considered in three dimension that one can recognize common pharmacophores. The chemical formulas do not display the relevant information for understanding the biological properties of a molecule.

articles

Bioisosteric Design of Conformationally Restricted Pyridyltriazole Histamine H2-Receptor Antagonists Lipinski CA J. Med. Chem. 26 1983

Cimetidine Example¶

The compounds represented here are H2-antagonists. The 2D chemical formula of a compound is unique; it may possess thousands of possible conformations. From the proximity of two chemical moieties in a 2D chemical formula, one cannot deduce that the two moieties are also close in 3D. Pharmacophores can be deduced only by considering the 3D molecular geometries of the compounds concerned.

Folded Conformation of Cimetidine¶

As revealed by X-ray analyses, cimetidine exists in a folded conformation (favored by the formation of an intra-molecular hydrogen bond between a nitrogen atom of the imidazole and a N-H group of the side chain). The biological activities observed can now be understood by considering this conformation for cimetidine that now mimics well the second molecule. Such analyses could hardly take place from the mere observation of the 2D chemical formulas of the molecules concerned.

2D Considerations¶

In some cases the recognition of common 3-D features between chemical compounds can be deduced by considering their 2-D chemical formulas. This is the case of polycyclic molecules having a rather planar geometry for which the 2-D formula visualizes fairly well the relative 3-D location of the different structural moieties of the molecule.

articles

Centrally Acting Emetics. 6. Derivatives of -Naphthylamine and 2-Indanamine Cannon JG, Kim JC, and Aleem MA J. Med. Chem. 15 1972

Example¶

The following example displays the structures of polycyclic dopamine agonists. One can easily recognize the common 'phenethylamino' moiety carried by the structure of dopamine. The pharmacophore appears to be in an extended conformation.

3D Superimpositions Must be Realistic¶

3D structural information is of high informational content, however it must never be misused. For example, when conformations of a compound are considered, they must be realistic. The population of the conformation must correspond to substantial quantities, otherwise the 3D rationale invoked would not make any sense. For example, the two molecules displayed here showed good biological activities and experimental evidence required the keto-derivative to have a well-defined conformation as shown on the next panel.

Misuse of Structural Information¶

A very good superimposition is obtained by aligning the second molecule. However, watch out! This requires the double bond of the second compound to be rotated to 120°! The view gives the illusion of providing some logic, however the information is of no value.

Managing Hypotheses¶

Initial Requirements¶

In pharmacophore-based drug design the molecules can be compared only if they have the same mechanism of action. More precisely the process of identifying common pharmacophoric elements is legitimate only if the molecules bind to the same receptor and in the same region of that receptor.

Same Mechanism of Action?¶

In principle, you can compare different molecules only if you have evidence that they act according to the same mechanism of action. Especially in a pharmacophore-based approach where very often the actual mechanism of action is a "black box", you might assume this is part of the working hypotheses - that the molecules actually act according to the same mechanism of action. This allows the comparison of the three-dimensional structures, and if convincing 3D structural similarities are found, this strengthens the validity of the working hypothesis.

articles

Chlorpromazine and Dopamine: Conformational Similarities that Correlate with the Antischizophrenic Activity of Phenothiazine Drugs Horn AS and Snyder SH Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 68 1971

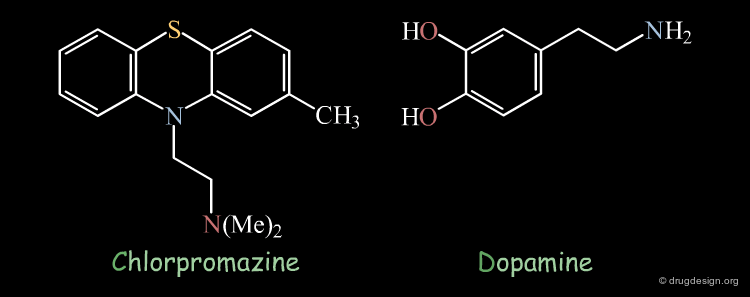

Chlorpromazine Example¶

Superimposition techniques have been very successful in elucidating the mechanism of action of the antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine. It was observed that the X-ray structures of chlorpromazine and dopamine were perfectly superimposed. On the basis of this discovery, it was suggested that anti-psychotic activity may be controlled by modulating central dopaminergic activity.

Tracking & Reconsidering Hypotheses¶

As soon as new results are obtained, it is necessary to re-assess current data assumptions, hypotheses and to check that they are still consistent with the current strategy. For that reason it is crucial to have a clear representation of facts and assumptions that were derived in order to be able to easily review the pathways that were pursued and to be able to possibly develop a new strategy.

Incorrect Hypotheses¶

Drug discovery moves on when working hypotheses become validated. Due to its empirical nature, drug research unavoidably generates hypotheses that are not always correct; some examples are given here. Drug design effort is always exposed to the danger of becoming trapped in the dead-end of incorrect hypotheses. Creative design occurs when hypotheses and analyses are carefully challenged.

articles

Molecular Features Affecting the Potency of Tricyclic Antidepressants and Structurally Related Compounds as Inhibitors of the Uptake of Tritiated Norepinephrine by Rabbit Aortic Strips Maxwell RA, Keenan PD, Chaplin E, Roth B and Eckhardt SB J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 166 1969

Bacterial Cell Wall Synthesis and Structure in Relation to the Mechanism of Action of Penicillins and Other Antibacterial Agents Strominger JL and Tipper DJ Am. J. Med. 39 1965

Example 1¶

In the first example 2D considerations permitted the formulation of an hypothesis that required the synthesis of new compounds that were expected to be very active. The authors were very much disapointed: the molecules they synthesized did not have the expected activities and abandoned the hypothesis considering it as incorrect. However, it has been shown that what was incorrect was the molecules that were designed, not the hypothesis! The reconsideration of this hypothesis at the 3D level allowed the design of different molecules that were synthesized and showed to have very good biological activities! (for the entire story go to E3.12.1 and the following pages).

Example 2¶

The second example is more subtle. The hypothesis was developed in 2D and then completed with 3D considerations, justified only with mechanical commercial models. The consequence of which was that tricyclic moieties with a "buterfly-like" shape were indispensable for the biological activities concerned. Precise computerized force-field minimizations invalidated this model and showed that the tricyclic moiety was not necessary at all. Non-tricyclic molecules were synthezized with a much more reduced pharmacophore which proved to have good biological activities (for the entire story go to E3.3.1 and the following pages).

Multiple Pharmacophore Hypotheses: Example¶

Obviously the quality of the hypotheses is a function of the data available. Incorrect hypotheses and the data they generate sometimes substantially increase the quality of the data. It very often happens that you have to consider several hypotheses that may be opposed or entirely independent. It may be useful to explore in parallel several hypotheses; the same goal can be achieved through entirely different hypotheses.

Dopamine Agonists: Where is the Pharmacophore ?¶

The two following molecules represent dopamine agonists. An interesting question is what is the common pharmacophore shared by these compounds. Two alternative ways were proposed for recognizing the pharmacophoric elements in these two structures (model A and model B) as presented in the next pages; it is however interesting to note that both interpretations have led to the discovery of two completely different families of compounds!

articles

Bicyclic and Tricyclic Ergoline Partial Structures. Rigid 3-(2-aminoethyl)Pyrroles and 3- and 4- (2-aminoethyl)pyrazoles as Dopamine Agonists Bach NJ, Kornfeld EC, Jones ND, Chaney MO, Dorman DE, Paschal JW, Clemens JA, and Smalstig EB J. Med. Chem. 23 1980

Centrally Acting Emetics. 6. Derivatives of -Naphthylamine and 2-Indanamine Cannon JG, Kim JC, and Aleem MA J. Med. Chem. 15 1972

Pharmacophore Model A¶

The Pharmacophoric Model A: In this case the pharmacophore is to the phenethylamino moiety, which is in an extended form and can therefore be easily superimposed. The problem with this hypothesis is that the hydrogens on carbon atoms indicated by an asterisk have opposite configurations.

Pharmacophore Model B¶

The Pharmacophoric Model B: In this model the pyrrole ring is selected to mimic the phenyl ring. The advantage of this model is that there is a greater stereochemical consistency than in model A; the hydrogens on carbon atoms indicated by an asterisk have now the same configuration.

Each Model Gave Good Results¶

The fact that two different agonist dopamine agents such as dihydrexidine and CY 208-243 were discovered based on different pharmacophore models illustrate that in pharmacophore-based drug design the validation of a given pharmacophore model and the discovery of molecules with great potential does not necessarily mean that other models cannot also lead to useful results.

Poor Initial Data: Too Many Hypotheses¶

When one has too many hypotheses and all the hypotheses are of the same importance, it is impossible to consider all of them simultaneously. At this point one has to search for ways to create additional data and thus reduce of the number of hypotheses. Systematic chemical modifications, combinatorial chemistry of diverse structures, systematic or oriented screening using a database of available compounds are examples of means currently used to enrich the quality of the structural data in a project of this type.

Validating Hypotheses by Chemical Syntheses¶

A chemical synthesis is sometimes undertaken to confirm or to reveal the validity of a given hypothesis. The following example illustrates how novel dopamine D2 modulator agents were rapidly discovered after the synthesis of a compound that was prepared to produce information on the bioactive conformation of the molecules concerned. Based on the structure of the reference peptide Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 (PLG), Analog 1 was found to be 1000 times more potent than PLG.

X-Ray Analyses¶

The X-ray crystal structure of analog 1 showed it to be in a conformation that is favored by the formation of a weak intramolecular hydrogen bond. However it was not sure that this X-ray conformation corresponded to the bioactive one of this molecule.

articles

Design, Synthesis, X-ray Analysis, and Dopamine Receptor-Modulating Activity of Mimics of the C5 Hydrogen-Bonded Conformation in the Peptidomimetic 2-oxo-3(R)-[(2(S)-Pyrrolidinylcarbonyl)Amino]-1- Pyrrolidineacetamide Baures PW, Ojala WH, Gleason WB, Mishra RK, Johnson RL J. Med. Chem. 37 1994

Dopamine Receptor Modulation by Conformationally Constrained Analogues of Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 Yu KL, Rajakumar G, Srivastava LK, Mishra RK, Johnson RL J. Med. Chem. 31 1988

Rigid Analogs Synthesized¶

In an effort to determine whether that conformation was responsible for the high biological activity of this compound the rigid analogs 2 and 3 were synthesized. The compounds showed to be very potent dopamine D2 modulator agents and confirmed the nature of the conformation of these agents when they bind to the receptor.

Browser of Dopamine D2 Agents¶

Receptor Mapping¶

The Role of Inactive Molecules¶

When a small modification of an active molecule leads to the complete loss of biological activity, this means that the "lock" does not accept the "key" anymore. The structural information associated with this analog is of high informational content. The data accumulated by the systematic exploration of the space available around an active structure can provide sufficient information and a precise idea of the stereochemical requirements of the receptor site.

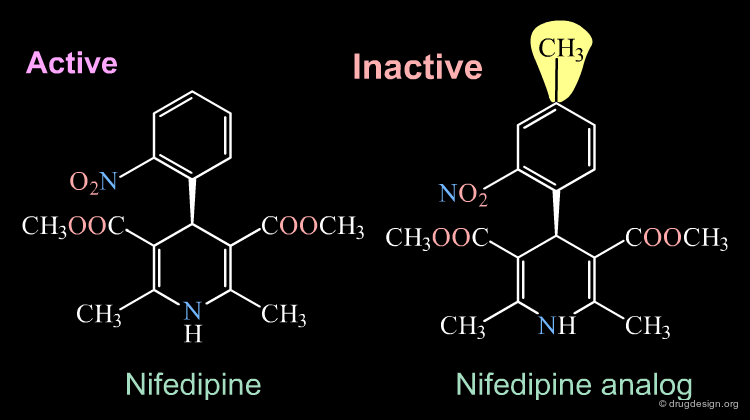

Inactive Analog of Nifedipine¶

Nifedipine is a well-known calcium antagonist used in the treatment of cardiovascular disorders including hypertension. When nifedipine is substituted in the para position by any substituent, the corresponding analog is completely inactive. With a para substitution on the phenyl, the molecule no longer binds to its receptor due to bumps that exist between the ligand and the receptor.

Rearrangement of the Bioactive Conformation¶

The addition of a methyl group in the 4-position of the structure of nifedipine leads to the complete loss of its biological activities.

Two Boat Conformations of Dihydropyridine Ring¶

The dihydropyridine ring of nifedipine can exist in two alternative boat conformations. The nitrophenyl substituent can therefore be in either the axial or equatorial orientation.

Preferred Conformation of Nifedipine¶

The preferred conformation of the nifedipine is where the phenyl substituent is in the axial orientation. In the methyl-4 nifedipine, the presence of the methyl group in position 4 modifies the conformational preference of the dihydropyridine ring (demonstrated by X-ray crystallography and by molecular mechanics) and the nitrophenyl group becomes equatorial.

Origin of the Inactivity Methyl-4 Nifedipine¶

The inactivity of the methyl-4 nifedipine is therefore explained by the new molecular geometry adopted by the molecule, that no longer fits the stereochemical requirements of the receptor.

Judging with Discernment¶

The examples presented in the previous pages showed that the introduction of a methyl group in different regions of the same active molecule can lead to entirely inactive molecules. In both cases it was due to an improper molecular geometry. However, in one case it was due to the induction of a conformational change, whereas in the second case the overall conformation was satisfactory, but the receptor's pocket was not large enough.

Good Understanding of Conformational Aspects¶

Paying particular attention to the consequences of small changes in a molecule is very important. An excellent understanding of the conformational possibilities of a molecule and the forces that control its geometry are essential for a correct interpretation of the observations.

The Active Analog Principle¶

When almost nothing is known about the stereochemical requirements of the receptor, one can try to develop a systematic analysis aiming at their identification. This strategy is called 'receptor mapping'. The union of all active molecules indicates the 'receptor-excluded volume', which is the volume not occupied by the receptor itself.

articles

A Unique Geometry of the Active Site of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Consistent with Structure-Activity Studies Mayer, D., C. Naylor, I. Motoc, and G. Marshall. J. Comput.- Aided Mol. Design. 1 1987

book

Marshall, GR, Barry,CD, Bosshard, HE, Dammkoehler, RA and Dunn, DA. ACS Symposium Series 112 RE. ACS 1979

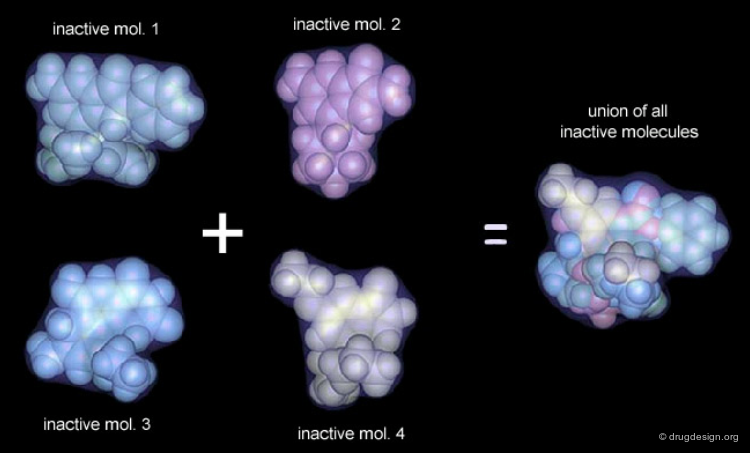

Receptor Essential Volume¶

Compounds with poor biological activities are defined in terms of unfavorable steric interactions with the receptor. The union of all inactive molecules defines a volume that is useful for operations that reveal the "receptor-essential volume", which is the volume occupied by the receptor.

Volumes with Favorable or with Bad Interactions¶

Mathematical operations (e.g. subtraction, union etc...) can be used with receptor-excluded and receptor-essential volumes to reveal volumes with favorable or with negative interactions with the receptor.

Active Analog Approach Browser¶

Example of Receptor Mapping¶

Although nicotinic agonists have similar structures, substantial differences in the relative activity exist. Whereas superimposition techniques did not indicate the reason for these differences, receptor mapping can explain the significant difference in activity between isoarecolone and nicotinic agonist

articles

((+-))- Octahydro-2-methyl-trans-5 (1H)-isoquinolone Methiodide: A Probe that Reveals a Partial Map of the Nicotinic Receptor's Recognition Site Spivak CE, Waters JA, Yadav JS, Shang WC, Hermsmeier M, Liang RF and Gund TM J. Mol. Graphics 9 1991

Receptor Map of Nicotinic Agonists¶

From the derived receptor map it can be seen that the active agonists fit inside the cavity of the receptor, whereas the inactive one (nicotinic agonist 4) does not completely fit due to steric hindrance of the hydroxyl group.

Two Generations of Pharmacophores¶

The Two Generations of Pharmacophores¶

There are several generations of pharmacophores. Pharmacophores of the first generation were very simple consisting of only two or three elements; they still continue to be used. The second generation is more sophisticated. With color-coded cones, spheres and other volumes, they represent hydrogen-bond donors or acceptors, structural fragments, permitted/forbidden regions. The colors distinguish between hydrophobicity, polarity, polarizability, and ionicity.

The First Generation of Pharmacophores¶

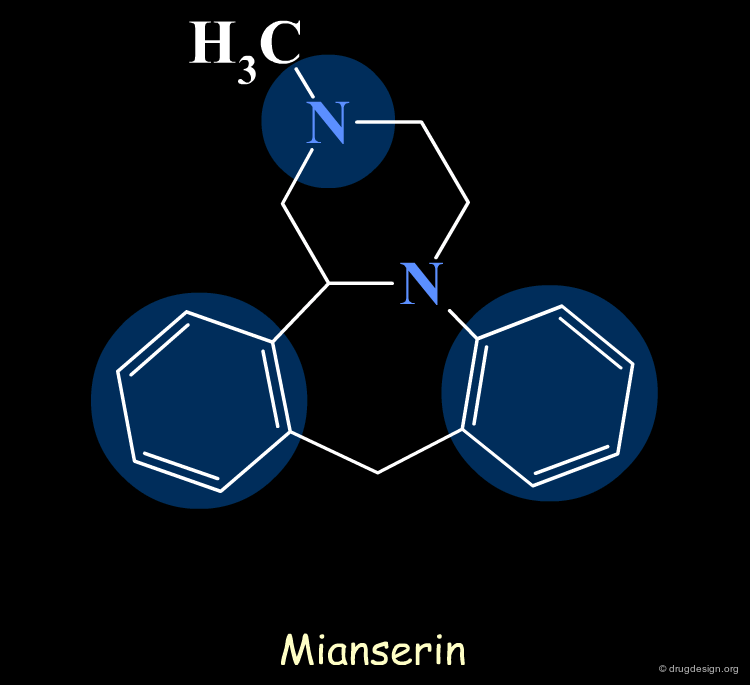

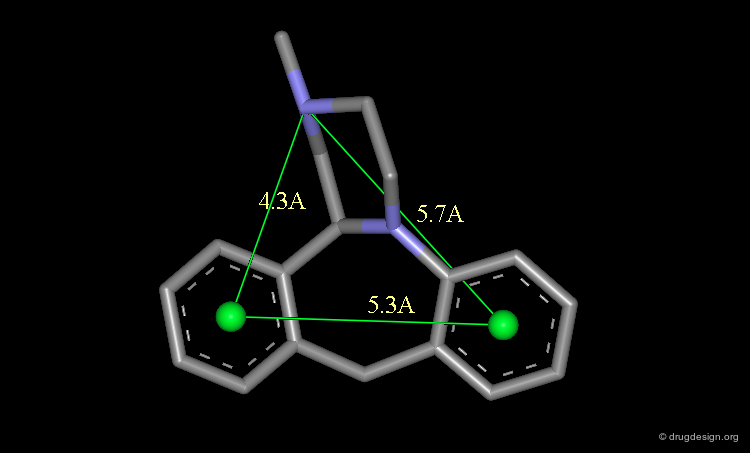

Pharmacophores of the first generation are defined by specifying atom types and interatomic distances. For example a pharmacophore model that was proposed for antipsychotic activities of mianserin and consisted of the following three elements.

Mianserin Pharmacophore in 3D¶

The following pharmacophore model was proposed for the selective binding to the sigma receptor.

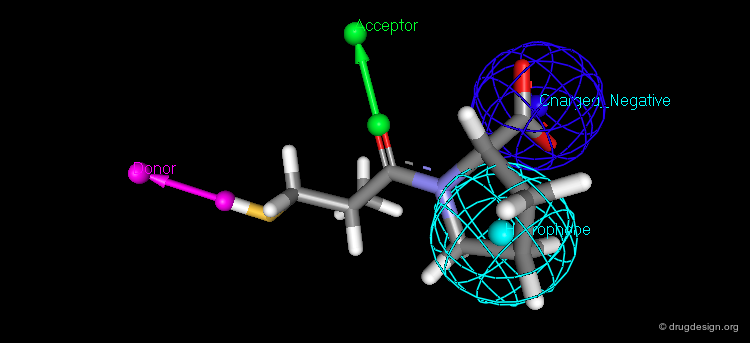

The Second Generation of Pharmacophores¶

Pharmacophores of the second generation are sometimes called functons. These functons are built by assembling substructures and chemical functions (e.g. hydrophobic, hydrogen bond acceptor or donor, ionizable group) and not only in terms of atomic positions as in the first generation.

Future¶

The concept of pharmacophore is continuously growing. The next generation will be an extension of the current situation, however translated in the space of numerical analyses with less emphasis on the visual aspects. A series of different numerical scoring functions will cover the whole space and control the different molecular features with their associated 3D distribution of physico-chemical properties such as: lipophilicity potential, electrostatic potential, dispersion forces, hydrogen-bond donors or acceptors, polarizability, ionicity, solvation, charge.

Summary¶

Pharmacophore-Based Drug Design Summary¶

In this section, the underlying concepts associated to pharmacophore-based drug design were discussed. The practical development of this approach covers several aspects; their exact nature can be summarized as follows:

Copyright © 2024 drugdesign.org